How Psychedelics and Your Gut Microbiome Might Work Together for Mental Health

A Summary of: "Seeking the Psilocybiome: Psychedelics Meet the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis" by Kelly et al.

Study: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9791138/

Introduction: A New Frontier in Psychedelic Science

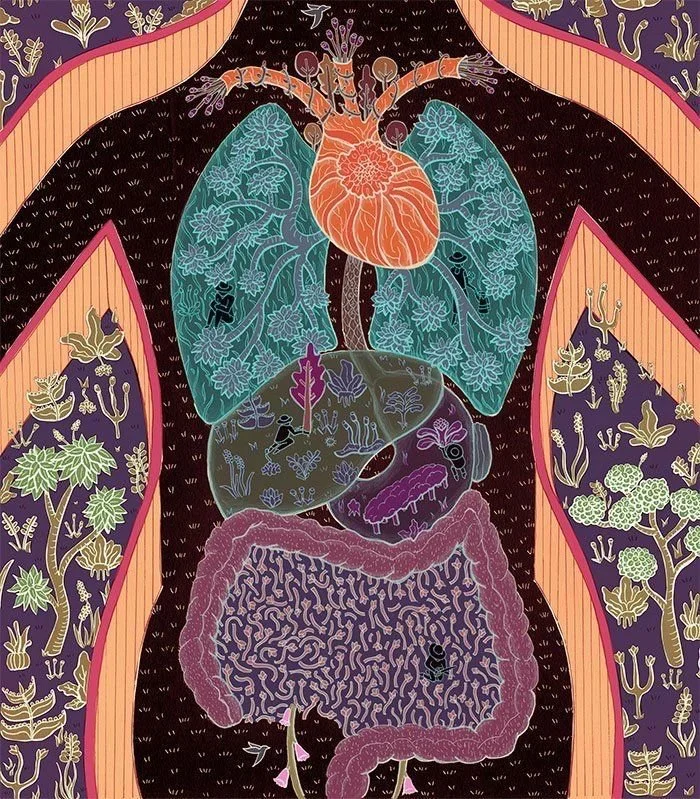

For years, scientists have been fascinated by how psychedelics like psilocybin (the active compound in magic mushrooms) affect the brain. But recent research suggests that these mind-altering substances may not be working alone—they might be interacting with the gut microbiome, the trillions of bacteria and fungi living in your digestive system.

This study explores how the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis—the communication system between your gut and your brain—might influence psychedelic therapy. Could optimizing gut health improve the effects of psilocybin or even predict who will benefit most from psychedelic treatment?

Psychedelics and the Brain: A Quick Recap

We know that psychedelics like psilocybin, LSD, and DMT work primarily by stimulating 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in the brain. This is what leads to altered perception, emotional breakthroughs, and sometimes lasting improvements in mental health conditions like depression, PTSD, and addiction.

However, the effects of psychedelics are not just about what happens in the brain—our entire body, including the gut, plays a role in the psychedelic experience.

Your Gut and Your Brain Are Always Talking

The gut microbiome is more than just bacteria helping with digestion—it’s a key player in mood regulation, stress response, and even cognition. The bacteria in your gut can produce neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which are the same brain chemicals influenced by psychedelics.

Scientists have found that people with psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, often have an imbalanced gut microbiome, with fewer beneficial bacteria and an overgrowth of harmful ones. Some key observations:

People with depression often have less butyrate-producing bacteria, which help reduce inflammation and support brain health.

Chronic stress and trauma can disrupt the gut microbiome, leading to a feedback loop of anxiety and low mood.

The gut microbiome plays a role in how the body metabolizes drugs, including psychedelics—meaning your gut health could affect how you process psilocybin.

This raises an important question: Could improving gut health make psychedelic therapy more effective?

How the Gut Might Shape the Psychedelic Experience

Psychedelic therapy typically happens in three phases:

Preparation: Getting mentally and physically ready for the experience.

Administration/Dosing: The psychedelic journey itself.

Integration: Processing insights and making lasting changes.

The gut microbiome may play a role in each of these phases:

Before the Trip: A balanced gut might help create a more receptive brain state, improving emotional resilience and reducing anxiety before the experience.

During the Trip: The gut can influence how psilocybin is metabolized, meaning microbiome differences may explain why some people have more intense trips than others.

After the Trip: A healthy gut can support long-term mental health improvements by helping regulate mood and inflammation.

This suggests that adjusting gut health before a psychedelic experience (e.g., through diet, probiotics, or prebiotics) might help optimize the therapeutic effects of the session.

Fungi, Psychedelics, and Evolution: A Strange but Important Connection

Fungi—including psilocybin-containing mushrooms—have played a crucial role in the evolution of life on Earth. Interestingly, some fungi don’t just affect humans but also alter the behavior of insects and other animals. For example:

The Massospora fungus produces psilocybin and cathinone (a stimulant) to control cicadas.

The Cordyceps fungus hijacks ants' nervous systems, forcing them to spread fungal spores.

This suggests that fungi and their psychoactive compounds have evolved to influence behavior, which raises the question: Could psilocybin have co-evolved with humans in ways we don’t yet understand?

Tryptamines and the Gut: The Missing Link?

Psilocybin is part of a group of compounds called tryptamines, which are closely related to serotonin. The gut is actually the body’s largest producer of serotonin, and some gut bacteria can even create their own tryptamine-based compounds. This means:

Certain gut bacteria might influence how psilocybin is broken down and absorbed.

The gut microbiome could shape the emotional and perceptual effects of a trip.

Microbial imbalances might increase the risk of psychedelic side effects, like nausea or anxiety.

These connections open up the possibility that modifying gut bacteria could improve psychedelic therapy outcomes.

Beyond the Brain: Psychedelics, the Immune System, and Inflammation

We often think about psychedelics in terms of their effects on thoughts and emotions, but they may also have a profound impact on the immune system. Studies show:

Psilocybin can reduce inflammation, which is linked to depression and chronic stress.

The gut microbiome helps regulate immune function, and imbalances can contribute to anxiety, brain fog, and mood disorders.

Some psychedelic compounds may even act as natural immune modulators, helping balance overactive immune responses.

This suggests that psychedelics don’t just heal the mind—they may also help restore balance to the body.

What This Means for the Future of Psychedelic Medicine

The idea that the gut microbiome could influence psychedelic therapy is new but exciting. If researchers can figure out exactly how gut bacteria shape the psychedelic experience, it could lead to:

Personalized Psychedelic Therapy: Using gut microbiome testing to predict who will benefit most from psychedelics.

Better Outcomes: Preparing for a psychedelic experience by optimizing gut health through diet, probiotics, and lifestyle changes.

New Treatments: Developing microbiome-based therapies that enhance or complement psychedelic medicine.

Mind, Body, and Microbes

Psychedelic therapy is often described as a journey into the self, but this research suggests it’s also a journey into our biological ecosystems. The gut, the brain, and even the fungi that produce psilocybin are all connected in ways we’re just beginning to understand.

If the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in how we think, feel, and experience reality, then healing isn’t just about what’s happening in the brain—it’s about nurturing the entire system. As science continues to explore the psilocybiome, we may discover that the key to unlocking the full potential of psychedelic therapy lies not just in the mind, but in the microbes that shape it.

Key Takeaways

Psychedelics like psilocybin don’t just affect the brain—they may interact with gut bacteria.

The gut microbiome influences mood, stress, and drug metabolism, which could shape the psychedelic experience.

A healthy gut may improve psychedelic therapy outcomes and reduce side effects.

Psilocybin and gut bacteria both produce serotonin-related compounds, suggesting a deeper biochemical connection.

This research could lead to personalized psychedelic treatments based on gut health.

The gut-brain connection has always been powerful—but with psychedelics, it might just be mind-blowing ;).

Jessica Fortner via Scientific American

References

Kelly JR, Clarke G, Harkin A, Corr SC, Galvin S, Pradeep V, Cryan JF, O'Keane V, Dinan TG. Seeking the Psilocybiome: Psychedelics meet the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023 Apr-Jun;23(2):100349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100349. Epub 2022 Dec 14. PMID: 36605409; PMCID: PMC9791138.

Aday, J. S., Mitzkovitz, C., Bloesch, E. K., Davoli, C. C., & Davis, A. K. (2022). Psychedelic drugs in the treatment of anxiety, depression, and PTSD: A review of the evidence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(2), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01312-8

Alcock, J., Maley, C. C., & Aktipis, C. A. (2014). Is eating behavior manipulated by the gastrointestinal microbiota? Evolutionary pressures and potential mechanisms. BioEssays, 36(10), 940–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201400071

Blei, F., Dörner, S., Fricke, J., Baldeweg, F., Trottmann, F., Komor, A., & Hoffmeister, D. (2020). Psilocybin biosynthesis revisited: Discovery of a new gene cluster in Psilocybe "Magic" mushrooms and its evolutionary implications. ChemBioChem, 21(4), 732–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201900664

Bogenschutz, M. P., Ross, S., Bhatt, S., & Baron, T. (2022). Percentage of abstinent days following psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(10), 953–962. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2096

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019). REBUS and the anarchic brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 71(3), 316–344. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.017160

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Giribaldi, B., Watts, R., Baker-Jones, M., Murphy-Beiner, A., Murphy, R., & Nutt, D. J. (2021). Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402–1411. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032994

Clarke, G., Grenham, S., Scully, P., Fitzgerald, P., Moloney, R. D., Shanahan, F., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2013). The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(6), 666–673. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.77

Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3346

Cryan, J. F., O'Riordan, K. J., Sandhu, K. V., Peterson, V., & Dinan, T. G. (2019). The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. The Lancet Neurology, 18(2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30458-5

Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., May, D. G., Cosimano, M. P., Sepeda, N. D., Johnson, M. W., Finan, P. H., & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

Gandy, S., Forstmann, M., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Timmermann, C., Luke, D., & Watts, R. (2020). The potential synergistic effects between psychedelic administration and nature contact for the improvement of mental health. Health Psychology Open, 7(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920978123

Goodwin, G. M., Aaronson, S. T., Alvarez, O., Arden, P. C., Baker, A., Bennett, J. C., & Zolkowska, D. (2020). Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402–1411. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032994

Inserra, A. (2022). Psychedelics and the microbiome: The role of gut-brain communication in hallucinogenic drug effects. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 859233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.859233

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2014). Long-term effects of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation: A follow-up study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(3), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2013.841098

Kelly, J. R., Clarke, G., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2021). Gut feelings: The microbiota-gut-brain axis as a key regulator of antidepressant treatment response. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(3), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyaa074

Kuypers, K. P. C. (2019). Psychedelic microdosing: A systematic review of research on low dose psychedelics (1955–2019). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.08.003

Nutt, D., Erritzoe, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2020). Psychedelic psychiatry’s brave new world. Cell, 181(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.020

Thompson, T., & Szabo, A. (2020). Psychedelics as immunomodulators: The need for clinical trials. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.01.009

Valles-Colomer, M., Falony, G., Darzi, Y., Tigchelaar, E. F., Wang, J., Tito, R. Y., & Raes, J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x