MDMA is different than Psilocybin, but how?

It feels appropriate to write about the love drug known as MDMA on Valentine’s Day!

Information about both MDMA’s and Psilocybin’s ability to support symptoms of depression and boost serotonin is widely circulating. Although some effects can be similar, they actually don’t behave the same way.

Here is a brief overview of how they differ mechanistically.

First, serotonin!

Serotonin (5HT), is often referred to as a "feel-good" neurotransmitter. It plays a role in regulating mood, anxiety, and happiness among other physiological functions.

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, with significant concentrations in the central nervous system (CNS), including in the brain and spinal cord, where they play key roles in mood regulation, cognition, and pain perception. These receptors are also prevalent in the peripheral nervous system and various peripheral tissues. In the gastrointestinal tract, serotonin is crucial for regulating motility and secretion, reflecting its nickname as the "gut's brain." Approximately 90% of serotonin receptors are found here. Additionally, serotonin receptors in blood vessels, platelets, the heart, and lungs influence blood pressure, clotting, heart function, and respiratory regulation. The receptors are classified into several subtypes, such as 5-HT1 to 5-HT7, each with specific distributions and functions, highlighting serotonin's broad impact on both physiological and psychological processes.

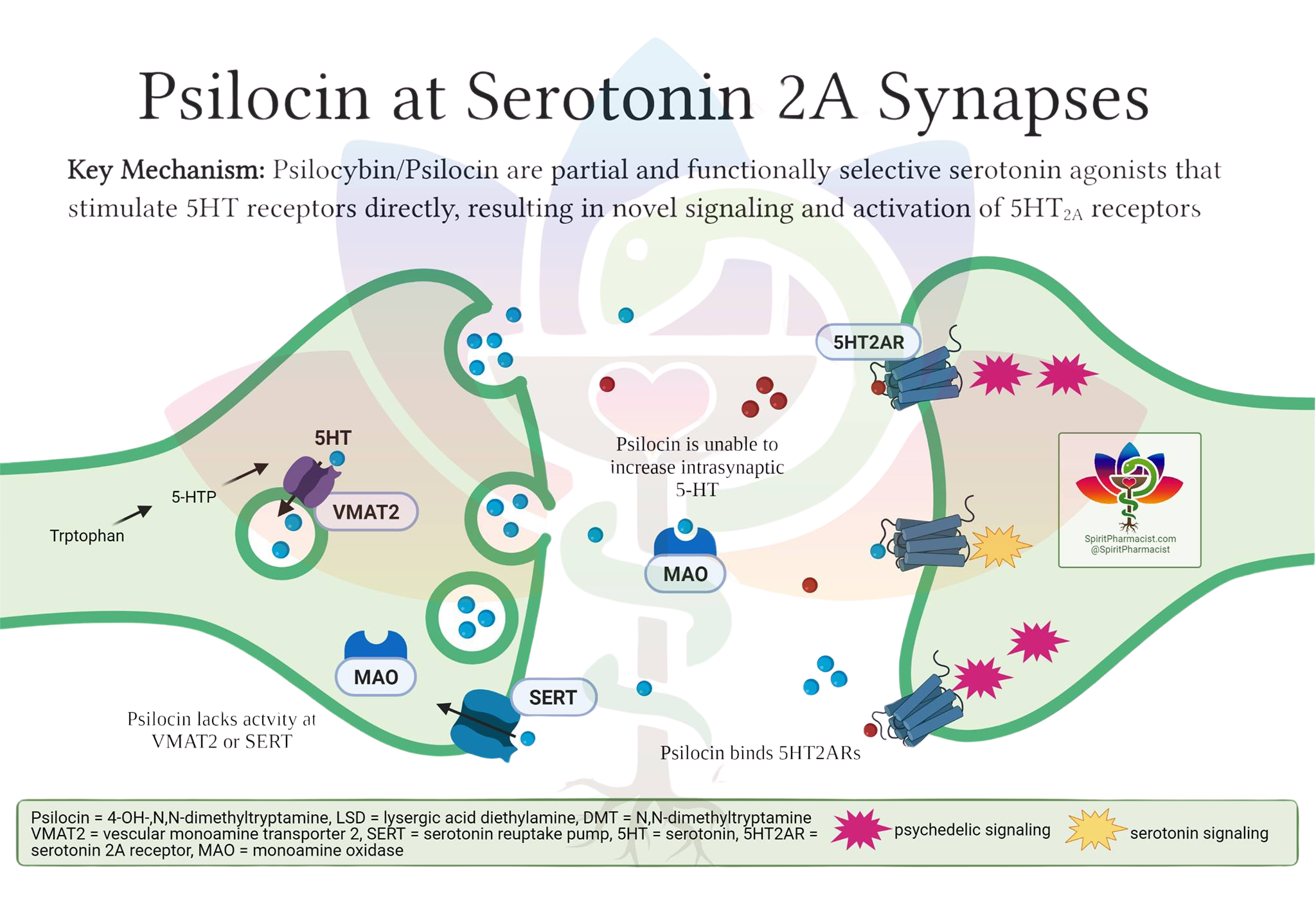

Psilocybin is a (partial) agonist of serotonin receptors (5HT-R), with highest affinity and functional activity at the 5-HT2A receptor.

This means that Psilocybin/Psilocin binds to 5HT-Rs and induces a positive biological effect.

It does not however cause the body to release more serotonin.

Its primary action is receptor agonism, leading to downstream effects on neural circuits and neuroplasticity.

Psilocybin is converted in the body to psilocin (active metabolite), which closely resembles serotonin in structure and can fit into the same receptor "locks" in the brain.

Think of this as a lock and key mechanism. Typically, serotonin (5HT), the key, will bind to its own receptors (5Ht-R), the lock. When psilocin (key) binds to 2A (lock), it activates the receptor, and directly triggers a series of changes in brain cell activity, leading to the unique changes in perception, mood, and thought associated with the psychedelic experience. This action is not due to an increase in serotonin levels, but rather because psilocin itself is acting as a stand-in for serotonin at these specific receptors, producing its effects by directly stimulating them.

MDMA, on the other hand, is not a direct agonist of 5HT-R, but does increase serotonin.

MDMA is not a key that fits into this lock. MDMA affects the transporters that are responsible for capturing serotonin to take it back into the cells for storage. These transporters are called SERT. By inhibiting SERT, more serotonin is available to bind to their receptors. MDMA can also cause more serotonin to be released into the presynaptic cleft, saturating the receptors and amplifying the effect of the neurotransmitters.

MDMA also inhibits the Monoamine Oxidase enzyme, which is responsible for breaking down and metabolizing serotonin. By blocking its metabolism, more serotonin is again available for binding. This is why MDMA can be contraindicated for individuals who take antidepressants of the MAOI class (Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors). Both of these taken together could amplify the inhibitory effect on the MAO enzyme, creating too much serotonin availability, potentially leading to Serotonin Syndrome. This risk also exists for combined use of Psilocybin and MAOIs, as serotonin is not being appropriately metabolised.

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition resulting from excessive serotonin levels in the nervous system, often due to medication interactions or overdose. Symptoms can range from mild (shivering, diarrhea) to severe (muscle rigidity, fever, seizures).

MDMA doesn’t only affect serotonin, but also the dopamine and norepinephrine transmitters. While, Psilocybin specifically acts on serotonin, MDMA has a broader effect. This non-specificity for neurotransmitters is an important reason why MDMA is showing so much promise for PTSD therapy. Dopaminergic activity helps enhance mood and emotional engagement, which are vital for therapeutic processes. Dopamine release during MDMA sessions can improve openness and emotional connection, facilitating the therapeutic exploration of traumatic memories and the development of positive associations, thus aiding in the healing process.

MDMA increases the release of norepinephrine as well, which affects energy levels and arousal. This increase can heighten emotional responses and physical sensations, potentially enhancing the therapeutic experience by allowing deeper emotional processing during PTSD therapy sessions. But it is also the reason by you may feel your heart beat increase and your body temperature rise.

SSRIs and MDMA

When SSRIs are taken concurrently with MDMA, the SSRI's blockade of the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) can inhibit MDMA's ability to release serotonin into the synaptic cleft. Since SSRIs occupy these transporters to prevent reuptake of serotonin, they can also prevent MDMA from accessing these transporters to release serotonin. This can lead to a reduction in the subjective effects of MDMA, as the primary mechanism through which MDMA exerts its effects (serotonin release) is impeded.

SSRIs can inhibit CYP2D6, an enzyme involved in MDMA metabolism, leading to increased plasma concentrations of MDMA. However, despite higher MDMA levels, the expected psychoactive effects are diminished due to SERT blockade. This attenuation may prompt some individuals to increase MDMA dosage, potentially raising the risk of toxicity

In summary, SSRIs blunt the effects of MDMA primarily by blocking SERT, reducing MDMA-induced serotonin release, while also increasing MDMA plasma levels via CYP2D6 inhibition. This interaction can reduce both the desired and adverse effects of MDMA, but may increase the risk of toxicity if higher MDMA doses are used.

SSRIs and Psilocybin

Due to psilocybin’s mechanism of direct 5HT-R agonism (key and lock), combined use with the SSRI class of antidepressants causes a dampening effect, rather than an amplifying effect. It has been noted that those utilizing psilocybin in therapy, may need to take a larger dose to feel its effect, if they are also taking prescription SSRIs.

Despite this attenuation of subjective effects, preliminary clinical data suggest that the antidepressant efficacy of psilocybin may be preserved when administered alongside SSRIs, with similar improvements in depressive symptoms and well-being observed in both SRI-treated and unmedicated groups. However, these findings are based on small, open-label, or survey-based studies, and larger, controlled trials are needed to confirm efficacy and safety in this context.

Pharmacokinetic studies show that SSRIs, such as escitalopram, do not alter psilocin plasma levels, suggesting the interaction is primarily pharmacodynamic at the 5-HT2A receptor level.

In summary, SSRIs blunt the acute psychedelic effects of psilocybin, but may not significantly diminish its antidepressant efficacy. The combination appears generally safe, though rare adverse reactions are possible. Further controlled studies are required to establish optimal protocols for coadministration in clinical practice.

SSRI stands for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor.

This class of antidepressants block the reuptake of serotonin into the cells, leading to a greater amount of serotonin available for binding to + saturating their receptors. This leaves less receptors available for psilocybin to bind to. When SSRIs are present, the competition or receptor down-regulation might diminish psilocybin's efficacy, potentially leading to a blunted psychedelic experience.

Recreation and Couple’s Therapy

MDMA has been used in recreational settings as well as in underground couple’s therapy. It is known as an empathogen and for its heart opening effects. From the dance floor to an intimate night in, MDMA fosters feelings of joy, love, and euphoria. It may make you dance extra hard and put a big smile on your face, but it can also support navigating trying times between partners by promoting trust, acceptance, and openness to share.

MDMA and The FDA

Recently, the MAPS organization filed a New Drug Application (NDA) with the FDA for the treatment of PTSD with MDMA Therapy. This NDA was recently accepted and the approval for this breakthrough therapy should be reviewed by August 2024. MAPS was established in the 1980’s with this very objective in mind. After being told countless times that this day would never come, MAPS founder, Rick Doblin, must be over the moon to be this close to approval after so many years of work.

—

I’m hopeful for the future of both PTSD and couple’s therapy. I urge those using MDMA in underground settings, be it for therapy or recreation, to practice safety first.

On this 2024 Valentine’s, practice self-love, acceptance, and openness.

—

References

1.

Pharmacological Interaction Between 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy) and Paroxetine: Pharmacological Effects and Pharmacokinetics. Farré M, Abanades S, Roset PN, et al. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;323(3):954-62. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.129056.

2.

The Effects of Fluoxetine on the Subjective and Physiological Effects of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in Humans. Tancer M, Johanson CE. Psychopharmacology. 2007;189(4):565-73. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0576-z.

3.

Acute Psychological Effects of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") Are Attenuated by the Serotonin Uptake Inhibitor Citalopram. Liechti ME, Baumann C, Gamma A, Vollenweider FX. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(5):513-21. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00148-7.

4.

Which Neuroreceptors Mediate the Subjective Effects of MDMA in Humans? A Summary of Mechanistic Studies. Liechti ME, Vollenweider FX. Human Psychopharmacology. 2001;16(8):589-598. doi:10.1002/hup.348.

5.

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): Interindividual Differences Due to Polymorphisms and Drug-Drug Interactions. Rietjens SJ, Hondebrink L, Westerink RH, Meulenbelt J.

Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2012;42(10):854-76. doi:10.3109/10408444.2012.725029.

6.

Qualitative Review of Serotonin Syndrome, Ecstasy (MDMA) and the Use of Other Serotonergic Substances: Hierarchy of Risk. Silins E, Copeland J, Dillon P. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(8):649-55. doi:10.1080/00048670701449237.

7.

Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use on 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-Assisted Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of the Evidence, Neurobiological Plausibility, and Clinical Significance. Price CM, Feduccia AA, DeBonis K. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2022 Sep-Oct 01;42(5):464-469. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001595.

8.

Drug-Drug Interactions Between Psychiatric Medications and MDMA or Psilocybin: A Systematic Review.

Sarparast A, Thomas K, Malcolm B, Stauffer CS. Psychopharmacology. 2022;239(6):1945-1976. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06083-y.

9.

Attenuation of Psilocybin Mushroom Effects During and After SSRI/SNRI Antidepressant Use.

Gukasyan N, Griffiths RR, Yaden DB, Antoine DG, Nayak SM.Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2023;37(7):707-716. doi:10.1177/02698811231179910.

10.

Interactions Between Classic Psychedelics and Serotonergic Antidepressants: Effects on the Acute Psychedelic Subjective Experience, Well-Being and Depressive Symptoms From a Prospective Survey Study.Barbut Siva J, Barba T, Kettner H, et al. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2024;38(2):145-155. doi:10.1177/02698811231224217.

11.

Content Analysis of Reddit Posts About Coadministration of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Psilocybin Mushrooms. Sakai K, Bradley ER, Zamaria JA, et al. Psychopharmacology. 2024;241(8):1617-1630. doi:10.1007/s00213-024-06585-x.

12.

Effects of Discontinuation of Serotonergic Antidepressants Prior to Psilocybin Therapy Versus Escitalopram for Major Depression. Erritzoe D, Barba T, Spriggs MJ, et al. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2024;38(5):458-470. doi:10.1177/02698811241237870.

13.

Psilocybin for Treatment Resistant Depression in Patients Taking a Concomitant SSRI Medication.

Goodwin GM, Croal M, Feifel D, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48(10):1492-1499. doi:10.1038/s41386-023-01648-7.

14.

Acute Effects of Psilocybin After Escitalopram or Placebo Pretreatment in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Healthy Subjects. Becker AM, Holze F, Grandinetti T, et al. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2022;111(4):886-895. doi:10.1002/cpt.2487.

15.

Serotonin Toxicity of Serotonergic Psychedelics. Malcolm B, Thomas K. Psychopharmacology. 2022;239(6):1881-1891. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-05876-x.

For more about MDMA and MAPS

https://doubleblindmag.com/lykos-therapeutics-maps/

https://doubleblindmag.com/mdma-maps-study-phase-3/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-021-01336-3

https://doubleblindmag.com/mdma-what-is-molly/

https://www.spiritpharmacist.com/blog/is-mdma-neurotoxic

Images provided by Spirit Pharmacist